In 10 seconds?The world's first malaria vaccine has received a historic nod from the WHO after already hundreds of thousands of children received it as part of pilot studies. Although it's not perfect, it attacks the shape-shifting disease in a novel way.

What's the news? In the last couple of years over 2.3 doses of the RTS, S (also known as Mosquirix) vaccine have been administered to children in Malawi, Ghana, and Kenya. After these pilot studies, in October 2021 the WHO gave the green light for large-scale vaccination to begin in entire sub-Saharan Africa, where most of the cases occur.

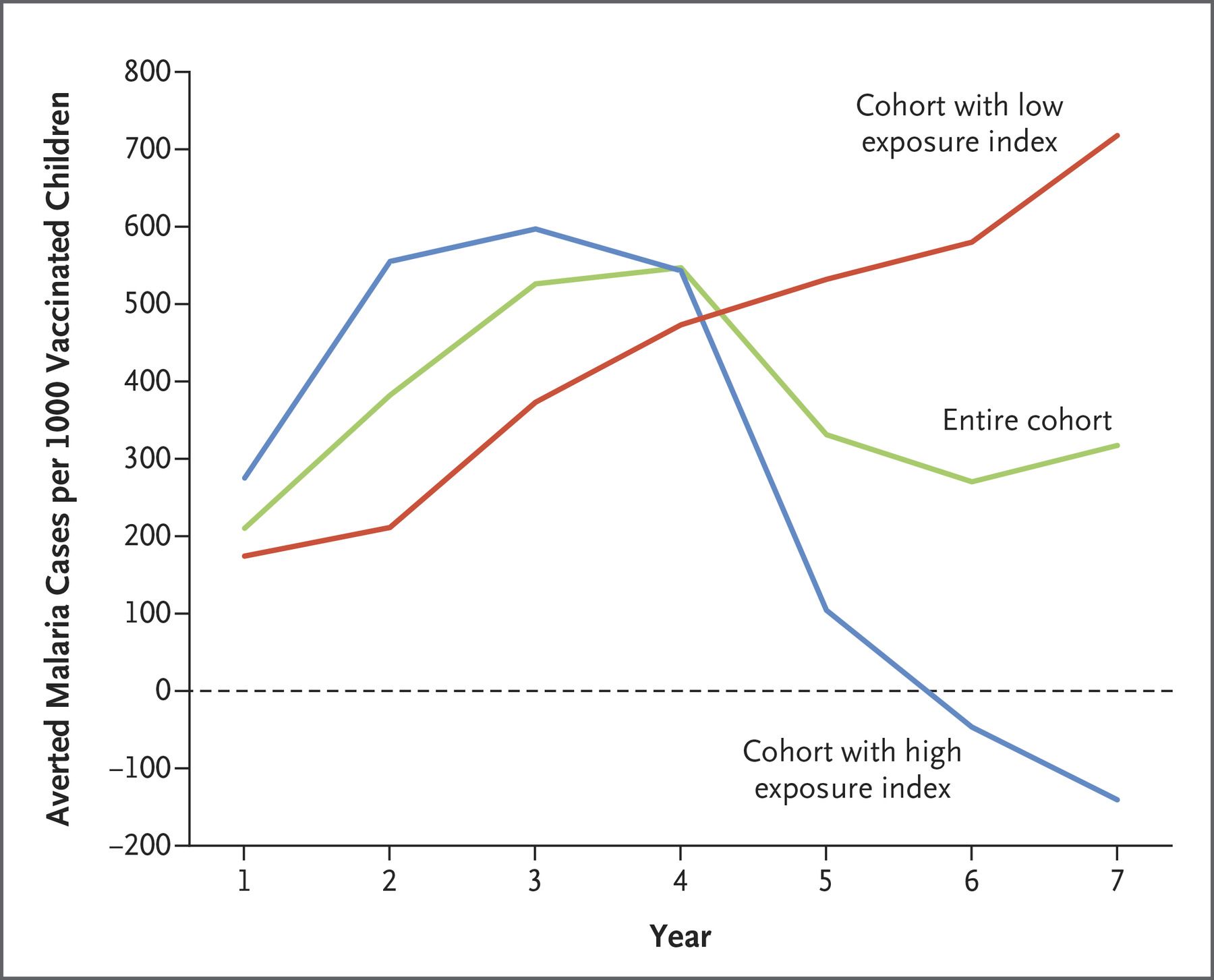

Wow, how does it work? RTS, S spots the disease-causing pathogen despite its ability to fool the immune system. It activates immune defenses in the first stage of malaria infection when the parasite Plasmodium falciparum enters the human body through a mosquito bite. The vaccine prevents the parasite from getting into the liver so that it can't mature and multiply before re-entering the bloodstream infecting red blood cells to spread the disease. According to the final results of a phase 3 randomized controlled trial, the vaccine was 56% effective in the first year and 36% effective over four years in reducing deadly severe malaria and hospitalization.

Why is this 'first stage' crucial? Malaria has three stages - one inside the mosquito that trasmits it, one in the human liver, on in the blood - and the parasite changes its shape throughout. This means the immune system has a difficult job chasing this intruder compared to a virus that is recognizable, having the same-looking proteins on its surface. (Think COVID-19-causing SARS-CoV-2, which is a mere wannabe in comparison). In the case of malaria, by the time immune cells figure out who the enemy is, it puts on a new uniform. The vaccine was designed to strike before this transformation occurs. There can be 60 different shapes in a malaria infection and creating a vaccine that recognizes them all has proved difficult.

Sounds like it’s not so effective? Well, according to clinical trials the efficacy rate is indeed modest, especially in the light of the current COVID-19 vaccines. RTS,S prevents about 3 in 10 life-threatening, severe malaria cases and reduces severe anemia – the most frequent cause of death in infected children by 60%. What will also affect its efficacy is its unusual schedule: it needs to be given four times - once a month for three months and then a fourth dose 18 months later.

How does it affect efficacy? Well, its relative success hinges on parents turning up with their child for the booster shot. The results of another randomized controlled trial published in 2021 give parents an incentive: in children who got 3 doses before the rainy season (the peak time for malaria) and an additional dose before the rainy season within the next two years, in conjunction with antimalarial drugs, malaria deaths were reduced by 73%.

How was the vaccine created? RTS,S was developed on the hypothesis that antibodies against the Circumsporozoite protein (CSP) – a secreted protein of the Plasmodium parasite – would protect humans from infection. Manuel Elkin Patarroyo, a Colombian immunology professor made the world's first attempt to create a synthetic vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum in 1987. After three decades of research, the vaccine was finally approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in July 2015 and by the WHO in 2017.

Are there any risks or side effects? Yes. Studies reported side effects which include pain, fever, and convulsions. Clinical trials also reported an increased risk of meningitis, cerebral malaria, and in some cases, death, calling for further investigation. But according to the EMA, the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risks and so it will be available to children under the age of 2.

So despite this, they are still rolling the vaccine out? Yes! It is a huge step forward. The director of the WHO's malaria program acknowledged that the vaccine was flawed but said the world could not afford to wait for a better option as the goal is to save as many lives as possible. Meanwhile, work is progressing on a modified version of RTS,S called R21. In a smaller-scale trial involving 450 children between 5-17 months of age, it showed 77% effectiveness in preventing malaria.

How big a problem is malaria?

The disease kills around 400,000 people around the world each year, the majority of them children. Most of these deaths occur in Africa, where more than 250,000 children under the age of 5 die every year, according to the WHO.

According to a modeling study, 23,000 children a year could be saved if all four RTS,S doses were administered according to the prescribed schedule.

Malaria enters the human body with the saliva of an infected Anopheles mosquito’s bite.

Not all mosquitoes are equally adept at transmitting the protozoan parasite Plasmodium from one host to another, but the female of the Anopheles can, spreading an often deadly and devastating disease. This is because Anopheles females need to feed on human blood to produce and nourish eggs.

There are currently several malaria vaccines in development.

Priyanka distilled 9 research papers to save you 31.5 hours of reading time with an evidence score of 3.8 out of 5.